INTRODUCTION

It is no secret that Detroit is a city that has experienced more than its share of challenges. From 2010 through 2019, Detroit went through a period of economic growth, though it was focused on a circumscribed area in and around the greater downtown business district and Midtown. Much of this economic resurgence has disproportionately benefited affluent whites, reflecting a migration back to certain areas of the city after generations of white flight. This was the landscape before March of 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic began to grip the country and exposed and exacerbated the racial chasms that were already in place. In Detroit, one of the most segregated cities in the country, the fallout of the pandemic not only highlighted the racial disparities in economics, housing, health care and education, but also it made them worse. This issue of Highlights focuses on the impacts of COVID on education in Detroit.

SCHOOL FUNDING

The lack of equity in school financing is a longstanding concern in Michigan for schools on the short end of the stick. For some time, it has been increasingly evident that Michigan’s high-poverty, lower-funded public-school districts, and charters do not receive the funds and resources they need to advance and educate their students at higher levels, and this was especially true during the pandemic. According to a 2020 State of Michigan Education Report, Michigan ranks in the bottom five states nationally for funding gaps that negatively impact students from low-income families. Although Michigan has one of the highest rates of concentrated poverty in the country, the state’s current funding system fails to provide financial resources specifically for districts with high concentrations of students from low-income backgrounds.

- Increases in per-pupil spending have been shown to improve education attainment, but Michigan ranks 24th nationally in per-pupil spending.

- Michigan is one of only 16 states that allocate less money to their highest-poverty school districts than the lowest-poverty school districts.

- Michigan’s baseline funding of $8,700 per student falls short of the $10,421 per-pupil cost estimated by the School Finance Research Collaborative.

- Michigan schools will receive a windfall of $3.7 billion in federal stimulus funding, on account of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Funding across districts and charters in Detroit is uneven, and more importantly, it is short-term. Federal relief dollars must be spent by September 2024.

Equal, Not Equitable Funding: The Michigan Legislature recently passed a budget that will allocate baseline funding of $8,700 for every student next year, regardless of school district. This compares with an estimated $10,421 per-pupil cost to educate a student in Michigan, based on a 2021 study by the School Finance Research Collaborative. Additional costs related to students living in poverty or enrolled in special education programs, etc., will only increase this figure. Students who live in high-poverty districts face more challenges and have greater needs and, therefore, require increased funding. Research has shown, for example, that it costs more to educate lower-income pupils, as well as English Learners (ELs) and students with disabilities. Additionally, students living in more affluent areas are more likely to benefit from funding outside of this budget.

Historically, Michigan has allocated less funding to its more impoverished school districts, and it is one of only 16 states that allocate less money to their highest-poverty school districts than their

lowest-poverty school districts. Therefore, equal funding does not level the playing field when students in these districts are already starting with fewer resources. Considering the needs of the students first when determining funding allocation will provide a much more equitable allocation than providing equal funding across districts. The need is unequal, and the funding should reflect the need.

Federal Relief Funds: Federal COVID-19 relief dollars will provide much-needed assistance that can be used to address issues that otherwise would continue unabated, or simply get worse. For example, the Detroit Public Schools Community District (DPSCD) now has approximately $1.2 billion in federal dollars to repair school buildings, fund programs to address learning loss from the pandemic, and boost teachers’ salaries. This represents a significant infusion of financial resources during a critical time; however, to provide some perspective, the District’s facilities repair shortfall alone is estimated to be in the neighborhood of $1.5 billion. Detroit’s charter schools will receive federal relief dollars, as well, though not at the same levels as DPSCD (although it should be noted that a sizable portion of the students they serve are also low-income students).

The fact that the funding resulted from the financial neglect the district has faced for decades, it was a victory for many Detroit students — but it is not enough. Bearing in mind that the federal stimulus funds are short term and must be expended by September 2024, there is more to be done to achieve equitable school funding in Michigan.

REMOTE LEARNING

The educational impact of the pandemic on the already distressed Black community in Detroit, has been profound. Prior to the pandemic, for example, in 2015, approximately 32 percent of white students in the 4th grade in the state of Michigan tested as proficient in reading, compared with just 9 percent of Black students. The same year, 34 percent of white students in the 8th grade were proficient in mathematics, compared to 5 percent of Black students and approximately 18 percent of Latinx students. There are other data points that illustrate the educational disparities in Detroit prior to the pandemic, but the point here is that, because of remote learning and a host of other factors, the COVID pandemic threatens to exacerbate these gaps in student achievement.

The overwhelming majority of students in Detroit returned to face-to-face instruction in the fall of 2021, following more than a year of remote learning. However, the situation has been fluid this semester, as the number of COVID-19 cases in Michigan ticked up. DPSCD, for example, closed schools for the entire week of Thanksgiving in response to the increase in COVID-19 infections, and also to address the need for mental health relief and allow more time to deep-clean the schools. The decision was then made to close schools on Fridays in December, citing the same reasons. A number of charter schools also returned to remote learning until the start of the new year. This suggests that many of the issues associated with remote learning outlined below will continue to be a challenge for Detroit students.

Technology: The pandemic turned homes into classrooms when safe in-school learning was not possible. The results of differences in “classroom” environments became especially important. Internet access was required to participate in classroom activities. In households where incomes exceeded $75,000, for example, 80 percent of these households had internet access. On the other hand, in households with incomes of $20,000 or less, approximately 30 percent had internet access. Compounding this disparity was another resource issue: access to a laptop. Without access to the very means of the instruction, students were unable to participate in any manner. Oftentimes, homework would go unfinished due to an inability to connect with the instruction. Even with the Connected Futures Project, which provided every Detroit Public School student with six months of internet and a tablet, issues remained. Due to prodigious expansion of charter schools, only about half of Detroit’s school-age children were even eligible to participate.

Another feature of technology that often leaves less affluent students at a disadvantage, even with internet access, is the low speeds and low-quality Wi-Fi signals that often accompany less viable and older infrastructure. Because of the highly segregated nature of Detroit’s housing patterns, Black students are far more likely to live in districts and neighborhoods where the housing stock and infrastructure are older and not as well-maintained.

Student – Teacher Interaction: The challenges associated with remote learning also have downstream effects. For example, students in remote learning environments spend less than half of the time in “live” learning and instruction. This leaves some economically challenged students in poorer districts at a significant disadvantage. In more affluent districts, there is a higher propensity to have planned remote learning as well as a higher tendency to have in-person learning spaces. These in-person students also receive a much higher level of interaction with the teacher and other students, which is superior to remote, solitary instruction.

Attendance: Pre-pandemic, school districts hosted two count days each year to determine the amount the state allocates to the district’s foundation allowance, making funding heavily reliant on attendance. Districts must offer at least 180 days and 1,098 hours of instruction and at least 75 percent of students must attend each day. Even then, more than half of Detroit students were considered “chronically absent,” missing 18 days or more of the school year. This can be challenging for students in lower-funded districts, as the pandemic has left families facing new socioeconomic challenges, loss and trauma, and ongoing health concerns.

Beyond the adverse impact of absenteeism on school funding, for obvious reasons it also has a tremendous impact on a student’s academic outcomes. Chronic absenteeism was exacerbated during the pandemic, as students struggled with access to instruction as well as the trauma and loss experienced in Detroit due to the pandemic. For example, the overall percentage of students who failed at least one class during the 2019-20 school year was about 36 percent. Comparing this with the 2020-21 academic year, when approximately 56 percent of students failed at least one class, we see a significant increase in the percentage of students failing. How these metrics will change now that children have returned to school remains to be seen.

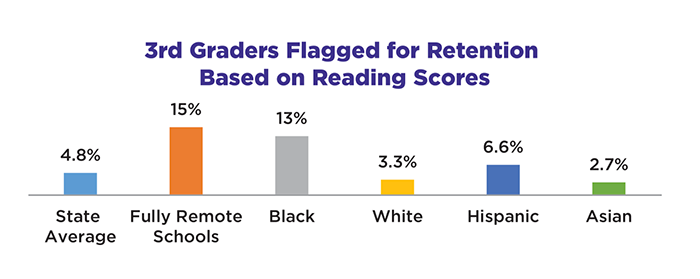

Academic Performance: Not surprisingly, during the last school year, many students grappled with emotional and learning challenges as a result of the pandemic. Academically, the year was especially challenging for Black and Brown students in Michigan, where approximately 13 percent of Black students were flagged for retention based on reading scores. In Michigan, state law recommends that students who are more than a grade level behind in reading at the end of the third grade be retained. While the overwhelming majority of DPSCD students do not take the test to assess third-grade reading levels, the need for additional academic support for Black and Brown students is clear.

MENTAL HEALTH

Perhaps one of the more insidious forces the pandemic has conjured is a debilitating level of stress. Families are experiencing significant levels of what has come to be known as socio-emotional stress, brought on by massive disruptions in everyday life and educational routines. This environment is, once again, exacerbated by the financial hardship that has accompanied the pandemic.

- The CDC reports that stress-related emergency room visits increased significantly between March and October 2020.

- Social isolation tends to lead to shorter attention spans and irritability, along with the fear of contracting COVID-19.

- 62% of DPSCD students surveyed reported symptoms of depression, with girls having higher rates of depression than boys.

- 23% reported having seriously thought about attempting suicide in the past year.

Barriers to Concentration: Limiting the income potential of already marginalized populations has placed housing and food insecurity on the front burner. School-age children within these households often have difficulty focusing on school when more existential needs are not being met. The adage that “it is hard to teach a hungry child” becomes more than just conventional wisdom. Students find it more difficult to concentrate for this cluster of reasons: food insecurity, housing insecurity, and, in some instances, lack of supervision. Because so many of the students in marginalized circumstances have parents who work in jobs that have been classified as “essential,” a lack of a parent or guardian presence contributes to an overall feeling of insecurity.

Pre-Existing Mental Health Conditions: Prior to the pandemic, many students attending DPSCD were already experiencing mental health issues. A recent survey of DPSCD students revealed that in addition to experiencing academic stress, more than half of the 11,000+ students surveyed (grades 8-12) also experienced symptoms of anxiety or depression. Consequently, these students were more likely to suffer from chronic absenteeism and found it difficult to study or complete schoolwork. Additionally, students who have experienced depression or anxiety, or have reported four or more adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), are also more likely to report having been suspended from school. Further complicating matters for Black students is a history of medical inequities and racism that creates barriers to accessing mental health services, in addition to barriers that include the social stigma associated with mental health treatment, not to mention the prohibitive cost.

COVID-19 Related Stress: The CDC has reported that the stress of COVID-19, and the attending disruptions of daily life have taken a toll on children’s mental health. From the onset of the virus in the middle of March 2020 through October 2020, the percentage of emergency room visits related to mental health (anxiety, panic attacks, sleeplessness, eating disorders, etc.) rose dramatically, according to the same CDC report. The peer reviewed article “Psychosocial Stress Contagion in Children and Families During the Covid-19 Pandemic” refers to a phenomenon called “stress contagion.” These stresses are further differentiated as spillover and crossover. “Crossover” refers to the stresses that are experienced by one member of the household, which then lead to increased levels of stress felt by or for another member of the household. In other words, witnessing significant stress elicits an empathetic response remarkably like the initial stress felt by another family member. “Spillover” occurs when outside stresses affect and compromise other functions. For example, the stress of working in a potentially infectious workplace (as many essential and frontline workers do) could negatively impact the ability to interact responsibly with other members in the household.

These competing stresses can be self-reinforcing. There are further psychological landmines when the effects of behavior are examined. Many school-age students rely upon schools for mental health support. It can be comforting to be gathered in a single place with friends and peers, and this often relieves anxiety and alleviates other potential issues. Social isolation, in combination with all the other stress factors, may simply act as another obstacle to mental health and, therefore, learning. Schools in more economically distressed districts will also have fewer resources with which to address all the issues heightened by the pandemic.

OTHER CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Beyond the challenges described above, myriad factors create additional challenges for Detroit students in the age of COVID-19. Economic inequality, employment-related issues including childcare, and housing insecurity are examples of COVID-19-related issues that are affecting many of Detroit’s students. Not surprisingly, if left unaddressed, these challenges can have adverse longterm impacts.

- Students affected by interrupted suboptimal schooling will face long-term losses in income.

- National economies that progress with a less skilled labor forces face lower economic growth.

- In the U.S., the education gaps could result in income losses of about $14 trillion over the next 80 years.

Economic Inequality: Detroit has the highest percentage of residents with incomes below $25,000, and the lowest percentage of high-income residents with household incomes greater than $150,000. Even before the virus hit, white families had approximately 10 times the wealth of the average Black family. Obviously, this economic inequality affects virtually everything. As school districts are still largely supported by property taxes, wealthy school districts will enjoy a substantial advantage in resources over more economically stressed districts. This, of course, affects classroom size and student-to-teacher ratio, which in turn affects the ability of a teacher to interact individually with students. It has been well documented that classroom size has a dramatic effect on the ability of students to learn. The wealth, or lack thereof, neighborhoods can then affect testing, learning, attendance, and motivation. Money especially matters for students from low-income backgrounds. Increases in spending have been shown to improve educational attainment and lead to higher wages and reduced poverty in adulthood, particularly for students from low-income backgrounds.

Work-Related Challenges: In school districts that are largely comprised of lower-income households, parents or guardians are more likely to have jobs that require in-person attendance and are much more likely to be classified as “essential.” Of course, this takes them out of the home, often during the day, many of these parents at greater risk of contracting the virus. Here is where yet another economic impediment presents itself: childcare. Already an issue across all economic strata, including affluent households, fewer resources makes identifying affordable, safe childcare even more of a priority need. Schoolchildren of certain ages simply cannot be left at home for extended periods of time, and it is often necessary for one parent either to stop or suspend working or take a shift that allows them to spend daytime hours with their children.

Housing Insecurity: In this maelstrom, economic disparities also present as housing insecurity. With truncated and often nonexistent income, the ability to pay rent or a mortgage is reduced. Homes that were owned now risk foreclosure, and eviction notices hang over the well-being of a family. Without relief, these families will be put into a vicious cycle of debt and recovery, never seeming to be able to save or get ahead. Dreams of college education give way to the immediate necessities of survival; in turn, this affects motivation, which in turn affects school performance. The cycle is never-ending. What is needed to break the cycle is something that goes beyond the status quo. It has been established that students in these distressed economic situations will be impacted emotionally, financially, and educationally. School-age children in the lower income brackets are often living in multigenerational households, which in some cases can relieve some of the stress (childcare, more income), but can also be riskier, as older generations are more susceptible to the virus.

OPPORTUNITIES & RECOMMENDATIONS

In closing, with the exception of remote learning, all the educational challenges presented here existed prior to, and have been exacerbated by the COVID pandemic. To address these challenges, what are potential opportunities or recommendations?

It is important to identify any promising policies, strategies, or practices, including those currently in place, as they may be present opportunities to build on, expand, or sustain. Potential opportunities and recommendations related to mental health and school funding that align with other, education-related research are listed below.

SCHOOL FUNDING

DPSCD students will certainly benefit from the infusion of federal COVID-19 relief funding. However, this is not a long-term solution, given that federal COVID funds will be spent over a two year timeframe. Considering this, a few potential, longer-term recommendations for school funding are outlined below.

- The only valid indicator of fairness in school funding is the parity of outcomes. Anything else is an attempt to paper over the inequality children face with some stingy legalistic definition of fairness and then blame them for the consequences.

- Provide equitable school funding based on student need. This could potentially look like at least 100 percent more funding for students with greater needs, such as low-income students and English Learners. Research indicates that in Michigan, an increase of up to 150 percent for low income students and English learners is needed to help close the achievement gap with more affluent students.

- Help eliminate funding disparities between wealthier and lower-income communities by providing equalization funding in high-poverty, low tax base districts. Increased funding for high-needs districts such as DPSCD will go a long way in helping to close the achievement gap

- Finally, there is much to be learned from other states whose school funding policies and practices are more equitable than those in Michigan. These lessons may prove beneficial in terms of making a case for change.

› Kansas may have done the most over the years to use rigorous statistical models to inform school finance legislation, as well as inform their state supreme court when ruling on the equity and the adequacy of funding .

› In Massachusetts, a student is considered high needs if they are designated as either low-income, an English learner (EL)/former EL, or a student with a disability. Educating a student who would fit into one or more of the aforementioned high-need categories requires more resources and, in turn, results in higher costs to provide high-quality education.

The associated extra resources and expenses can offer more learning support, leading to more equitable learning opportunities. Therefore, a key indicator is identifying high-needs student populations when evaluating school funding fairness among states.

› What gets funded matters just as much as how much it is funded, making local control of funding formulas and accountability metrics vital. The Chicago Public Schools, for example, entered a one-year, $33 million contract with the police department, diverting vital resources away from starved schools in need of school nurses, guidance counselors, social workers, and even teachers. Culturally sustaining curriculum, healthy school meals, early childhood education, high-quality teaching and counseling, low teacher-student ratios, and rich before- and after-school activities should be taken into account when allocating funds.

› Increase resources and supports to address the challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic that have recently exacerbated educational inequalities. For many student populations, remote learning has resulted in several challenges. Select populations include students with disabilities, homes with unequal access to technology, families unable to assist their children who are learning from home, and students who have experienced adverse childhood experiences without the typical school interventions.

› Addressing students’ non-academic needs by attending to the whole child would help the most vulnerable students during this current crisis. Educating the whole child would focus on allocating funds that could be used for wraparound services. Such services could include health care, crisis interventionists, family community supports, and counseling while increasing the number of counselors, school psychologists, nurses, truancy officers, and social workers within the schools to help meet students’ non-academic needs.

› Community schools typically are open before and after regular school hours as well as on the weekends so they can provide wraparound services such as dental and health care, parent education, internships, and family social work, and integrate communities into school decision-making processes. This approach, however, requires blending funding streams that extend beyond school financing, as well as better empirical evidence to understand the processes and practices that best serve children and their communities in different contexts.

› Over the last several decades, while state government support for maintaining quality schools has declined, labor unions have increasingly shifted their bargaining and lobbying priorities to include quality of education policies — such as bargaining for more recess, less time on testing, better school infrastructure, more attention to equity issues — and have led efforts across the country to secure more per-pupil funding. Moving forward, unions will continue to play a vital role in school policy and funding.

MENTAL HEALTH

- TRAILS Detroit (Transforming Research into Action to Improve the Lives of Students) is a multiyear, three-tiered, school-based initiative designed to improve students’ social and academic outcomes by meeting their mental health care needs. TRAILS is currently available to students in all DPSCD schools. Given the mental health challenges faced by so many DPSCD students due to the COVID-19 pandemic and systemic racism, efforts to sustain this initiative indefinitely should be a very high priority for policymakers and the philanthropic sector.

- Providing access to mental health services is a major step forward, but it does not guarantee that students in need will seek out and utilize those services. Overcoming the stigma around mental health is critically important. Education, including peer-to-peer education to increase students’ awareness and understanding about mental health, recognizing why mental health important, and knowing how to seek help, is critical.

- Wraparound services such as those described above, under School Funding, also have a role to play in addressing mental health concerns. Providing services that address the whole child in every school, such as access to counselors and therapists, will go a long way toward ensuring that children enter the classroom ready to learn.

The data presented here underscores the adverse impact COVID-19 has had on education in Detroit. It also highlights potential opportunities to address these challenges, some of which New Detroit may choose to explore further.

SOURCES

C. Kirabo Jackson, Rucker C. Johnson and Claudia Persico, Boosting Educational Attainment and Adult Earnings: Does School Spending Matter After All?, Education Next, vol. 15 no. 4, Fall 2015. http://educationnext.org/boosting-education-attainment-adult-earnings-schoolspending/

Mauriello, T. (2021, June 29). Will Michigan finally have equal school funding? Maybe, if House bill clears Senate on Wednesday. Chalkbeat Detroit. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https:// detroit.chalkbeat.org/2021/6/29/22556247/michigan-house-equity-school-funding-billsenate

Michigan’s School Funding: Crisis and Opportunity. (n.d.). Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://michiganachieves.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/”12/2020/01/EducationTrust-Midwest_Michigan-School-Funding-Crisis-Opportunity_January-23-2020-WEB. pdf-emci=ae9e7f87-1d89-ec11-a507-281878b83d8a&emdi=559d7c90-b089-ec11-a507281878b83d8a&ceid=401142

School Mental Health in Detroit Public Schools Community District. A needs assessment from TRAILS and the Youth Policy Lab (n.d.). Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://storage. trailstowellness.org/School_Mental_Health_in_DPSCD.pdf

Hanson, M., & Checked, F. (2021, December 3). U.S. Public Education Spending Statistics [2022]: Per pupil + total. Education Data Initiative. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https:// educationdata.org/public-education-spending-statistics#michigan

Higgins, L. (2021, May 17). ‘I don’t want the flame to go away’: Why more Detroit parents are pushing for in-person learning. Chalkbeat Detroit. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https:// detroit.chalkbeat.org/2021/5/17/22441201/i-dont-want-the-flame-to-go-away-why-moredetroit-parents-are-pushing-for-in-person-learning-

Ron French, More Michigan Third Graders Struggled to Read Amid COVID Remote Learning, Bridge Michigan, September 7, 2021. https://www.bridgemi.com/talent-education/more-michigan3rd-graders-struggled-read-amid-covid-remote-learning

Adam McCann, Financial Writer. States With the Most and Least Equitable School Districts. (n.d.). Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://wallethub.com/edu/e/states-equitable-schooldistricts/76723

Press release: SFRC releases updated report on cost to educate a Michigan student during, post COVID-19. School Finance Research Collaborative. (2021, June 2). Retrieved December 17, 2021, from https://www.fundmischools.org/press-release-sfrc-releases-updated-report-oncost-to-educate-a-michigan-student-during-post-covid-19/

A New Round of Federal Education Relief, but the Same Inequitable Formula. Citizens Research Council of Michigan, January 11, 2021. https://crcmich.org/a-new-round-of-federaleducation-relief-but-the-same-inequitable-formula.

DeGrow, B., Ben DeGrow | December 2, 2021, & Ben DeGrow | January 13, 2022. (n.d.). Detroit District Buries Charters in Federal Covid Relief. Extra millions don’t provide students with in-person earning. Mackinac Center.Mackinac Center. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://www.mackinac.org/detroit-district-buries-charters-in-federal-covid-relief

Pulkkinen, L. (2021, November 5). Federal Money is the only hope for school districts that can’t raise local funds for facilities. The Hechinger Report. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://hechingerreport.org/detroit-schools-are-effectively-barred-from-raising-funds-torepair-their-buildings-federal-money-is-the-citys-only-hope/

DeGrow, B., Ben DeGrow | March 18, 2020, & Abigail Elwell | August 19, 2021. (n.d.). Detroit charters get 29% less funding than district. New study highlights K-12 revenue inequities in 18 cities. Mackinac Center. Retrieved February 15, 2022, from https://www.mackinac.org/detroitcharters-get-29-less-funding-than-district